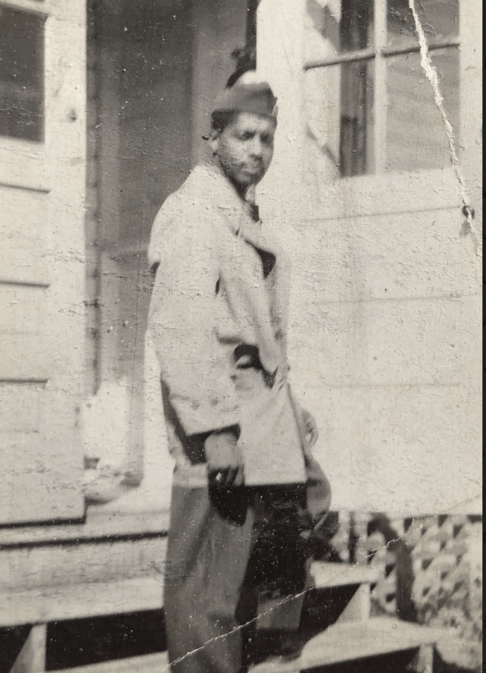

“Pop-Pop, did Black soldiers like you actually fight in World War II?” My grandfather, a WWII U.S Army combat veteran, lifted his shirt to reveal the scar left by the shrapnel that destroyed one of his kidneys. He looked at me and said, “I lost a lot of friends.”

[pullquote posiition="right"]Until my conversation with Pop-Pop, I wasn’t sure if Black soldiers fought in the war.[/pullquote] In school, I had been learning about WWII through the lens of a white soldier. My history textbook displayed the heroic pictures of white soldiers charging the beaches of Normandy and white Marines raising an American flag on Iwo Jima. There was nothing in my history classes that showed me that Black soldiers were actively involved in the same fight.

In fact, Blacks played a significant role in the war effort with more than 2.5 million registered for the draft. For the record, it was not just white troops that served under General George Patton in Europe; the 761st tank battalion, otherwise known as the “Black Panthers,” was an all-Black tank unit attached to General Patton’s command. This is the same battalion that received 391 decorations for its acts of bravery in combat.

It is important to note that during World War II, the U.S. Military was completely segregated. It was not until 1948 that President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 to officially integrate the military. My grandfather served in an all-Black Army unit not by choice, but by order.

Pop-Pop, who passed away in 2003, did not delve further into what he encountered while fighting in the Pacific Theater. Instead, he spent more time talking to me about his stateside experience as a Black soldier. There was one story in particular that stayed with me. Prior to being deployed to the Pacific, my grandfather and his fellow soldiers, all Black, decided to visit an off-base diner. As they walked in, a white man quickly ran up to them and declared “We don’t serve N-words here!” Pop-Pop looked straight at me and said, “Mind you, we were all wearing our Army-issued uniforms.”

My AP U.S. History teacher never provided me with such a dichotomy to debate. Why would Black soldiers, who faced such stark racism, risk their lives and limbs to raise a flag? Why did the white shop owner view the Black soldiers defending his freedom with such disdain?

When I discuss World War II in my classroom, I make it a point to share my grandfather’s story and pose these very questions to my students. [pullquote]Engaging my students in authentic learning involving race and country provides them with a wealth of information and a context they need to interpret the society we live in.[/pullquote] And ethnic studies and other similar programs, with curricula that address racism, enhance the academic achievement and critical thinking skills of students of color and white students alike.

Teachers like me need to bring such opportunities to learn into our classrooms, not just during Black History Month but throughout the entire academic year. I encourage teachers to explore Facing History & Ourselves, an organization that helps teachers transform their curriculum in a way that is more equitable for students of color. It has a rich array of curriculum and resources to help examine the role that race has played during pivotal moments in U.S. History.

The stories of Black soldiers can be used as inspirational and authentic catalysts for civic engagement. A great place to start is the story of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only all-Black unit that stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Teachers can utilize document-analysis reading strategies to personalize this story by learning about one of its members, Cpl. Waverly Woodson, Jr., a Philadelphian and Army medic who, even while suffering from multiple wounds, treated close to 200 men on Omaha Beach.

Although Cpl. Woodson received a Purple Heart and Bronze Star, he was never awarded the Medal of Honor. Students may be interested to know that there is ongoing bipartisan legislation in the U.S. Senate to posthumously award the Medal of Honor to Cpl. Woodson. It would be powerful if teachers can spark civic engagement by having their classes compose advocacy letters in support of this initiative.

By making a conscious decision to cover such material, we tap into the rich experience that our students of color are bringing into the classroom. You never know, someone in their family may have fought alongside my grandfather, flown as a Tuskegee Airmen, or stormed the beaches of Okinawa as a Montford Point Marine.

Ross T. Hamilton, Jr. teaches 12th grade government and civics at Building 21 High School in Philadelphia. He is a 2021-2022 Teach Plus Pennsylvania Policy Fellow.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.