I used to harbor a lot of rage toward my son’s kindergarten teacher.

When I first realized that my son, then a first-grader doing school remotely from our living room couch, couldn’t read even the simplest words, my first call was to his warm, kind kindergarten teacher.

Even though she was struggling with remote teaching, she made time to help him. “Tailoring his reading to his interests can go a long way,” she said. “Have you tried getting him some books about airplanes?”

“He can’t read the word ‘pin,’” I responded. “How’s he supposed to read the word ‘airplane?’” Why wasn’t this obvious to her?

“Do you think he could have dyslexia?” I asked, fighting my rising panic. “I don’t know,” she responded. “I don’t really know much about dyslexia.”

She had a master’s degree in education and a post-graduate fellowship in teaching reading. How could she not know anything about dyslexia?

Eventually, I learned how to teach my son to read myself. But I didn’t stop being angry at his teacher until recently.

The fourth episode of Sold a Story opens with the story of Lacey Robinson, a teacher who was once a struggling reader herself. She learned the value of phonics when she was a girl. But then, in graduate school, she studied and worked with Lucy Calkins, the author of Units of Study in Reading and Writing—the curriculum used at two of my kids’ elementary schools.

Like the good student she was, she trusted her professor was the expert. She abandoned phonics for Calkins’ “balanced literacy” practices, which included teaching children to use context and picture clues to identify words. It took years for her to realize Calkins’ approach was wrong.

If Robinson, who knew the value of phonics from her own experience, took years to realize her professor’s reading methodology was wrong, is it any wonder my son’s kindergarten teacher had not yet begun to doubt her received wisdom?

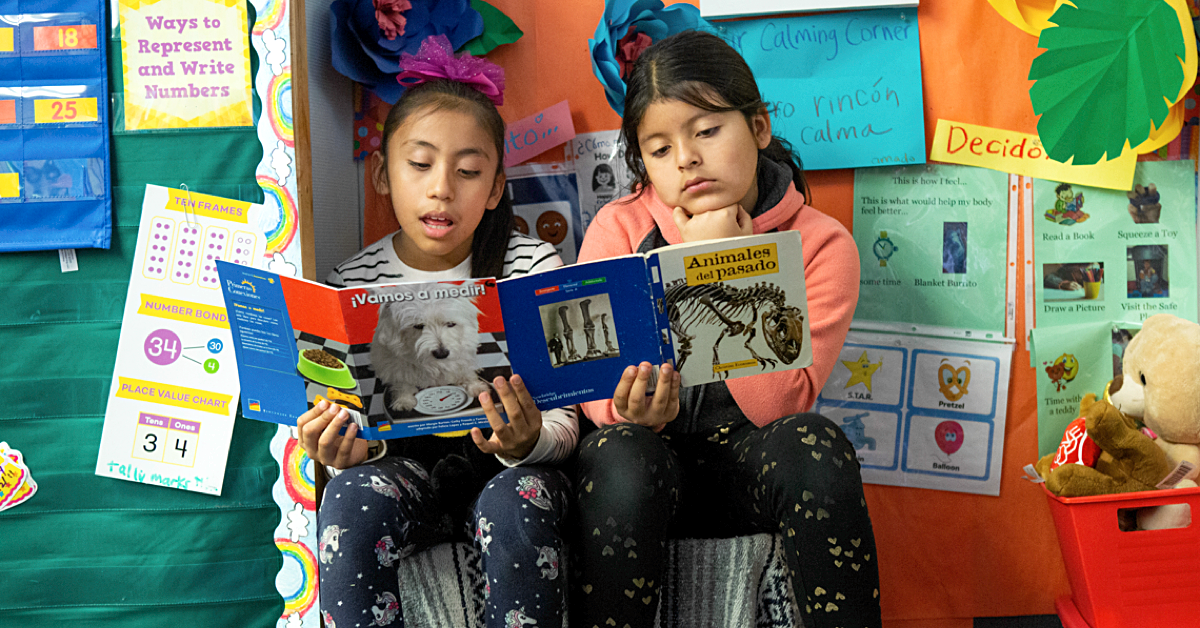

Most K-2 teachers cannot read all the research about instruction in every subject area. They teach not only reading and writing, but math, social studies, and science. During the past two years, they’ve taught in a hurricane of the pandemic, trauma, and social instability. Relying on experts and the curriculum they develop would seem a wise use of their limited time.

Generally speaking, teachers do not choose their curriculum. Ordinarily, school districts choose both the literacy curriculum and the accompanying professional development. Usually, principals hold teachers accountable for implementing the curriculum. If teachers deviate, there can be professional consequences. Teachers also are held accountable for their students’ performance on standardized tests.

For an image of what this means on the ground: imagine that teachers are expected to build a ship during a hurricane.

Not only has no one taught them to build the ship, but they have also been provided faulty blueprints and shoddy training in shipbuilding. The tools they have been given are a broken hammer and a rusty, blunt saw. Their boss will be dropping in occasionally to make sure they are following the blueprints and using the tools. If the ship sinks, everyone will blame them—as I had blamed my son’s kindergarten teacher.

Hanford’s podcast makes it clear illiteracy is a systemic problem—one that is embedded in the multiple institutions that affect how children learn to read. School boards, school administrations, and, yes, teachers all share some responsibility. However, she also makes it clear that the experts who should—and perhaps did—know better bear disproportionate responsibility.

“I assumed there was research behind this curriculum,” a teacher said in Sold a Story. This is a reasonable assumption.

Noted authorities Irene Fountas, Gay Su Pinnell, and Lucy Calkins all earned doctorates and hold professorships. They know how research works and how to do it themselves. They were supposed to keep up with the research in their field. None of them can say that they were unaware of the research. If they were unaware, they chose their ignorance.

Rather than abandon ship, some teachers choose a more difficult path. They pay out of pocket to learn what they should have learned in their degree programs and professional development. They implement their own curricula, often evading their principals’ oversight. They speak out about curriculum flaws, sometimes endangering their jobs or promotions.

As heroic as these teachers are, they should not have to go to such lengths to re-learn how to teach reading. They should have been able to count on the experts to keep abreast of the research and update their curricula accordingly.

These teachers, more than anyone else, were ‘sold a story.’ That includes my son’s kindergarten teacher. We need to save our criticism for the so-called experts who were sellers of poor reading instruction.

Tisha Rajendra is a professor, mom, PhD; ethicist; linguist; literacy advocate and tutor.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.