I am a special education teacher with 17 years of experience in the classroom and a parent of two children with dyslexia. Recently, I learned that my daughter’s teachers have been modifying their coursework for the whole class in response to the pandemic. This makes sense since virtual and hybrid learning have been so stressful and challenging for students.

But I was shocked to learn that many of these teachers thought their general supports for all students in the pandemic met the call for modifications in my daughter’s 504 plan. That plan identifies the individual supports she needs, as a result of her learning disability, to participate fully in school.

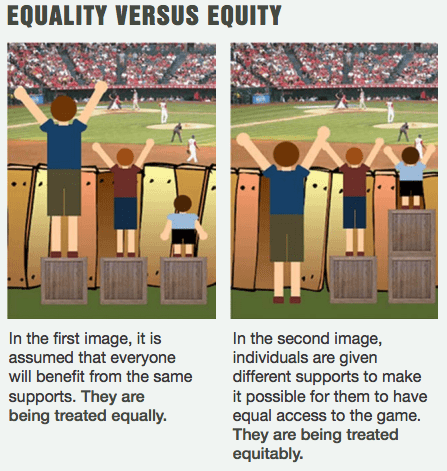

The minute I realized what was really happening, the image of equity as students on boxes came to mind. General modifications for an entire class are equality, not equity. When general modifications are all teachers offer, students with 504 plans and IEPs are still not getting equity. “How many other students is this happening to,” I wondered.

For many years I have fought to ensure that my children’s teachers understand the nature of their hidden disability, but this year has been different. This year, the fence got taller. Here’s how: [pullquote]Given that students across the board are struggling with anxiety, attention and focus, teachers are taking measures such as reducing text lengths and amounts of notes/writing, or assigning little or no homework for all students.[/pullquote] In my children’s middle school, many teachers and administrators think these overall course modifications are enough to meet the needs of students like my daughter.

Those modifications were enough in prior years, so they should be enough now, the thinking goes. But that thinking misses the reality that kids like my daughter, who were using those modifications successfully in prior years, are now also more stressed, anxious, depressed and struggling with focus.

Think about the image to the right—depicting past years’ consistent implementation of 504 Plan and Individualized Education Plan (IEP). It shows supports allowing all children to see over the fence by providing them the crate or two they need to raise their eye level up to the same level as other students. Now make the fence two feet taller.

As a teacher, when I modify course assignments for all students this year, with a taller fence, all I have done is put a crate under the tallest student. When I picture this scenario in my mind, I now see the first child in the blue shirt standing on a crate able to see over the taller fence. These modifications for all students have perhaps provided a necessary boost to the general population of students who may not normally need support.

The problem I discovered is that the other two children, who normally needed one or two crates to see over the fence at its previous height, now need two or three crates to see over the taller fence. The question is, have those crates been added?

In my daughter’s case, they have not. This means that in a year when all students are experiencing added stress and anxiety, students with disabilities, who normally struggle, may be left even further behind than usual, with even more stress, and still unable to see over the fence.

[pullquote position="right"]Teachers this year are working so hard, but they need to dig deeper for children with disabilities.[/pullquote] If it was necessary to modify the syllabus and course work for all students, given the challenges of virtual or hybrid learning, it is still necessary for teachers to provide students with 504 plans and IEPs additional, personalized supports beyond those. Just as the average student needs additional support this year, so do students with disabilities.

For example, a teacher may be teaching a modified course that has fewer lab periods due to hybrid learning. This reduction in the number of labs doesn’t mean that the remaining lab reports are any easier for a student to complete. If anything, these reports have gotten harder because they now need to be completed using PDF annotation tools so they can be turned in online.

Plotting the points on a graph still requires keeping all the numbers straight in your head while tracking across an axis looking for the second point, for which you are also trying to keep the numbers straight in your head. If a modified 50-point graph could yield the same observations as a 100-point graph, my daughter should have this particular lab modified to meet her brain where it is. The fact that there are fewer labs to complete this year for everyone is totally unrelated to my daughter’s need for this particular assignment to be modified.

In English class, a large assignment may be broken down into individual segments to support all students by making the workload more manageable in a virtual learning environment. This does not change the fact that each of these writing assignments may be a stressful experience as a student with dyslexia struggles to put their understanding of the content on to paper without the informal check-ins and as-needed support that might have been accessible if the work was completed in a classroom. Perhaps this assignment could have been further modified so that three of the five components were written and two were able to be submitted as audio or video recordings where the student defines and explains the components verbally.

When it comes to the fence analogy, my daughter and other students with disabilities are still shorter than most students in the class. They need those shortened assignments, copies of notes, and extra scaffolds for organization and time management—now making school manageable for the regular education population—even more modified.

They might need copies of in-class work and notes from class beyond what they were given last year since it is even harder to follow along and keep up online without that preferential seat near the teacher to help them to stay on task. They need even more assistance with organization and time management in addition to flexible options that go beyond just reading and writing to show what they know and have learned.

The bottom line is my child, and millions of others, still have a disability, and that disability has been exacerbated by the pandemic and its impact on schools. These students still need additional crates or support to see over the same fence as their peers.

LauraMarie Coleman is a mother of two children with dyslexia and a special education teacher with 17 years of experience, including time in the classroom and as a literacy and math instructional coach in Binghamton, New York. She currently works for the curricula developer Great Minds, supporting teachers and schools as they implement the Eureka Math curriculum.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.