The state has our hands tied. Kids are disrespectful and defiant. There’s absolutely nothing we can do to punish them that bothers them except spank them.

Those are the words of Pollock Elementary School teacher Erica Firmant as read by her husband, Louisiana State Representative Gabe Firment, during a legislative session last week. The bill proposed—House Bill 324—would have banned corporal punishment in public schools; in other words, it would have protected the safety and dignity of Louisiana’s children from state-sanctioned paddling.

Unfortunately, the bill failed to garner the votes necessary to pass.

Recently, news stories of school paddlings have shocked most of America’s educators. After all, only 19 states permit administrators to paddle students, and among those state, 70% of all paddlings occur in just four: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas. When cell phone footage of the brutal paddling of a six-year-old girl surfaced from Florida, CBS Morning News covered the story in all its horror. The CBS anchors’ shock mirrored much of the country’s: In a profession rooted in research-based best practices, how is there any justification for striking a child?

Through this lens, the news from both Louisiana and Florida appears aberrant—something sensational and viral. However, [pullquote]the truth is this: paddling students in the American South is so commonplace that simply challenging the practice is unthinkable.[/pullquote]

For all y’all living outside the Bible Belt, here are three myths about the topic of school-sanctioned violence that we at Arkansans Against School Paddling would like to debunk for you:

For many educators in states like Massachusetts, Michigan, California, and New Jersey, where padding was banned in 1867, there exists no frame of reference for conversations about hitting children in schools; their teachers never hit them, and they, in turn, have never hit their students. Simply put: Their states’ legislative bans on corporal punishment in schools broke a cycle of violence, rendering the topic “extreme” or “antiquated” for future generations.

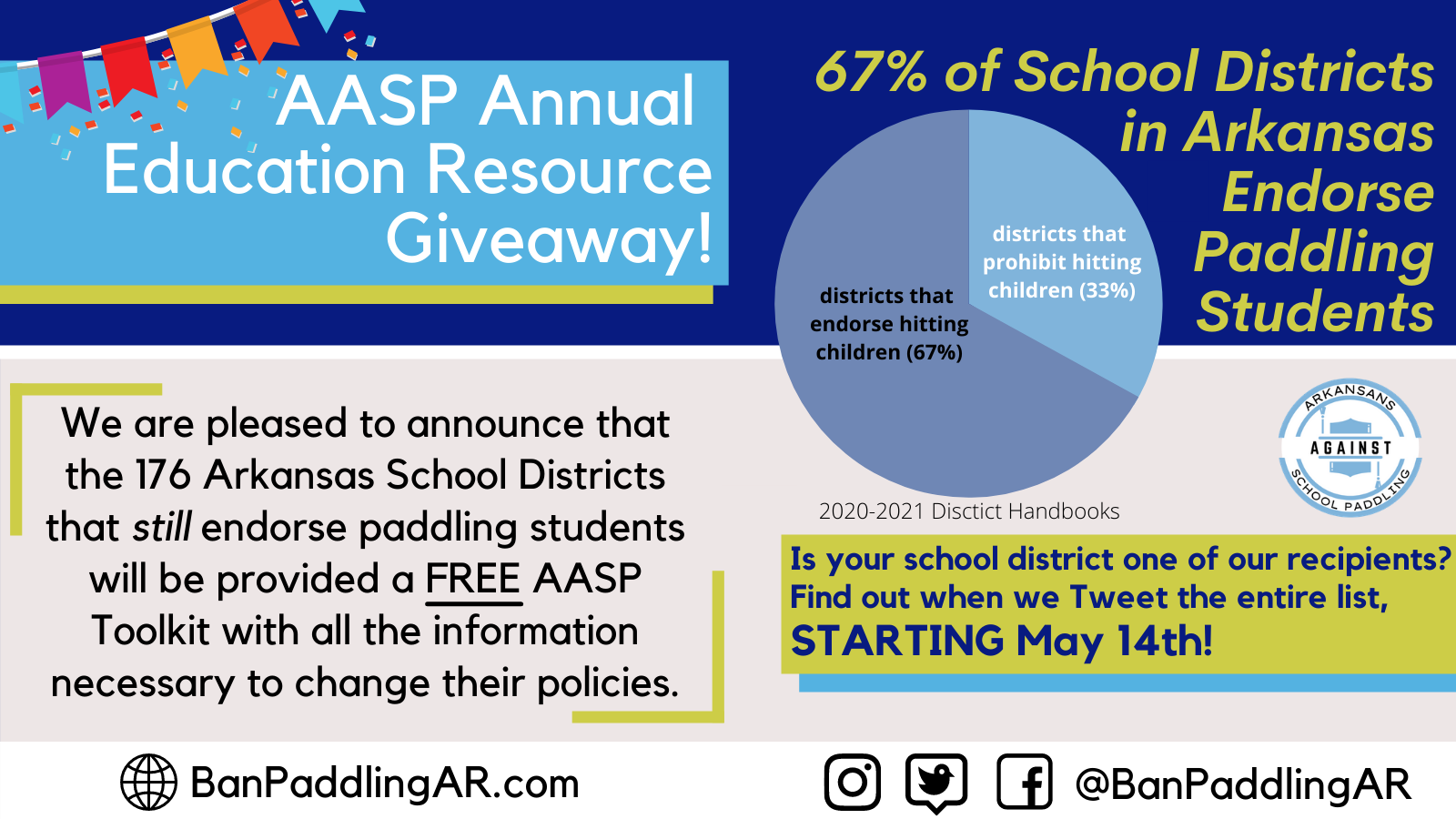

Meanwhile in states like Arkansas—in 2021—discipline policies in 67% of school districts still endorse hitting children. Arkansas’s students can be paddled for a number of reasons: from excessive tardies to “rough play.” And the administering of “licks” or “swats” is often based on the child’s age, sex, or “ability to bear the punishment”—an invisible pain threshold which never takes into account the lasting psychological trauma corporal punishment can cause.

[pullquote]Both the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics oppose corporal punishment.[/pullquote] According to researchers, paddling students can induce toxic stress, similar to that of ACEs, resulting in impulsivity, defiance, and cognitive problems. And yet, roughly 100,000 students are paddled every year in America’s public school system.

To frame the issue of school paddling as solely “cultural” would misrepresent both science and history—and that lazy framing only perpetuates the problem. First, let’s recognize some facts: in states that practice such corrective violence, Black students are two-three times more likely to be struck. And although a students’ parent or guardian might approve of the punishment, paddling students is a proven legacy of white Supremacy.

In her book “Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America,” Dr. Stacey Patton recognizes corporal punishment as a manifestation of intergenerational trauma—rooted in slavery and sustained by racial injustice—that plays an integral role in the school-to-prison pipeline.

Here’s another shocking statistic: [pullquote]In half of schools that administer corporal punishment, students with disabilities are more likely to be paddled.[/pullquote]

State laws that permit the hitting of children in schools are as oppressive and inequitable as some state-mandated tests, technology and broadband disparities, and white-washed curriculum. No one defends the SAT or ACT by reframing criticism as a “culture war”—so let’s not let the perpetrators of corrective violence against children reframe it that way, either.

Paddling students is not a “Southern problem”—it’s an American problem. As educators, we don’t reduce other social scourges—like police brutality—by localizing them. We don’t say “that’s a Minnesota problem” or “that’s an urban problem.” Instead, we recognize modern injustice as the inevitable result of our country’s centuries-long indifference. We work to recognize our own complicity and to disincentivize learning that doesn’t ensure a safer world for everyone.

As Americans, our interconnectedness is indisputable. Our principles are not demarcated by state lines, and chief among them is this: Children are our most vulnerable population. And it is our responsibility—as educators, as Americans—to ensure that they inherit a worldview not warped by institutionalized violence.

So, tweet your outrage! Share articles online about the risks of paddling students. Educate your colleagues about the issue. And engage in conversations with the same passion and bravery as you demonstrated in your comments about the senate runoff in Georgia and former President Trump’s border wall in Texas. And follow organizations like ours: Arkansans Against School Paddling.

Our website helps families identify which school districts in the state endorse hitting children. As an organization, we provide those districts with all the free resources they need to change their policies.

On behalf of children everywhere, we hope America’s educators—as well as Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona and First Lady Dr. Jill Biden—will take a stand against corporal punishment in 2021.

Kaya Henderson leads the Global Learning Lab for Community Impact at Teach For All. There, she seeks to grow the impact of locally rooted, globally informed leaders, all over the world, who are catalyzing community and system-level change to provide children with the education, support, and opportunity to shape a better future. She is perhaps best known for serving as Chancellor of DC Public Schools from 2010-2016. Her tenure was marked by consecutive years of enrollment growth, an increase in graduation rates, improvements in student satisfaction and teacher retention, increases in AP participation and pass rates, and the greatest growth of any urban district on the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) over multiple years. Most recently, Kaya has served as a Fellow with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, a Superintendent-in-Residence with the Broad Leadership Academy, a coach with Cambiar Education, and a Distinguished Scholar in Residence at Georgetown University. Kaya’s career began as a middle school Spanish teacher in the South Bronx, through Teach For America. She went on to work as a recruiter, national admissions director, and DC Executive Director for Teach for America. Henderson then served as the Vice President of Strategic Partnerships at The New Teacher Project (TNTP) until she began her tenure at DCPS as Deputy Chancellor in 2007. A native of Mt. Vernon, New York, Kaya graduated from Mt. Vernon Public Schools. She received her bachelor’s degree in international relations and her master of arts in leadership from Georgetown University, as well as honorary degrees from Georgetown and Trinity University. Her board memberships include The Aspen Institute, The College Board, Robin Hood NYC, and Teach For America. She chairs the board of Education Leaders of Color (EdLoC), an organization that she co-founded.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.