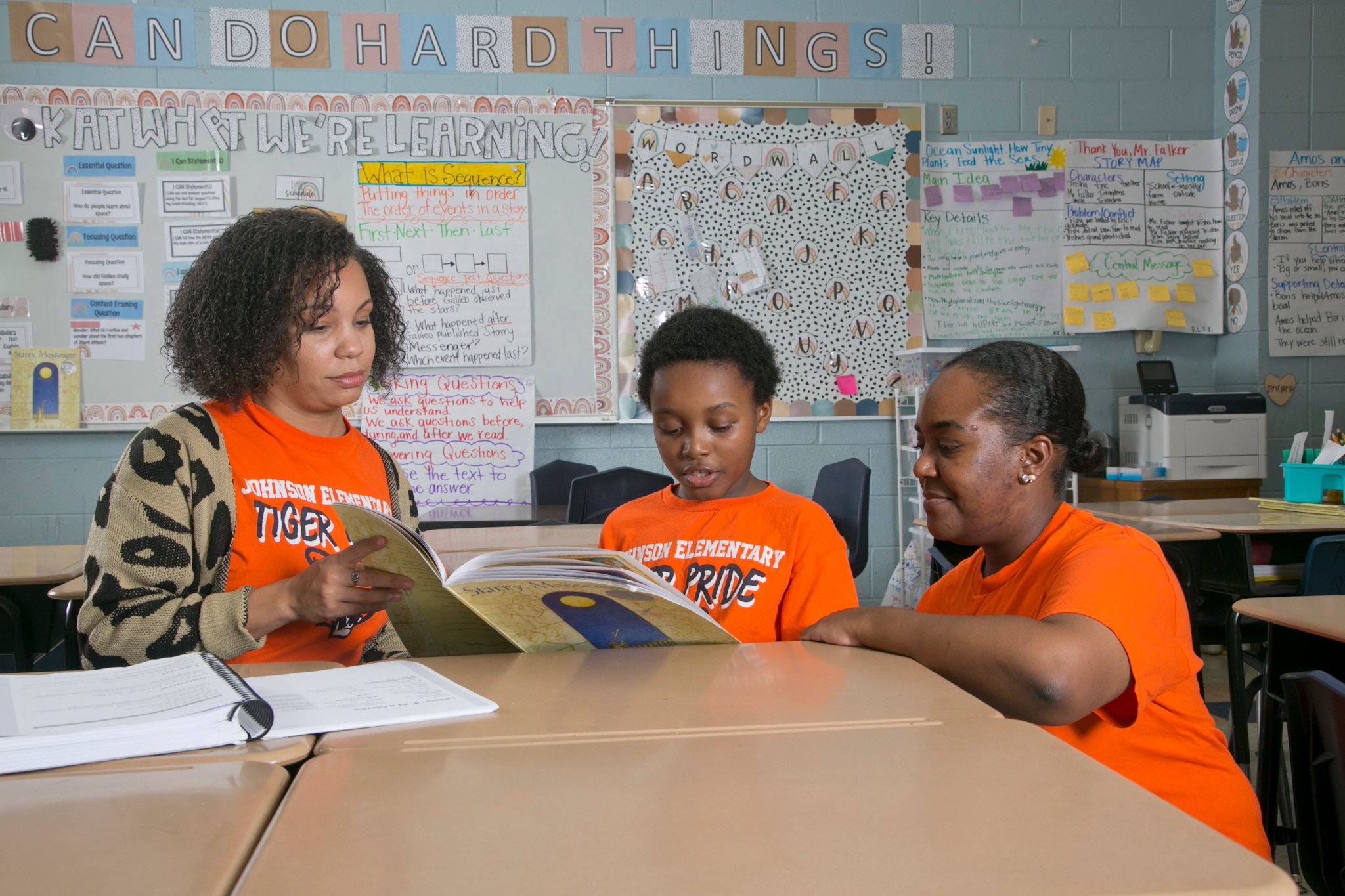

Cora-Lisa Weathersby’s son Cameron loves to read. But last year, when the Jackson, Mississippi, third grader was assigned weekly passages of challenging text, filled with unfamiliar words, Weathersby noticed her advanced reader was prone to skip over it quickly—maybe so he could get to his beloved Diary of a Wimpy Kid and Captain Underpants books faster.

Cameron’s third grade teacher at Johnson Elementary School, Barquita Stanton, said students read the challenging text passages every day for a week, at school and at home, to improve fluency. In class they all read in unison, a kind of “choral reading” technique used to build fluency.

“Before we read, we look for punctuation, we pause at certain punctuation marks, circle vocabulary words,” Stanton said. “We read with our fingers, don’t read too fast or too slow.”

“Choral reading” is one of the approaches Johnson Elementary is using to move beyond the basics of decoding words to build other skills needed for reading, like fluency, building vocabulary and background knowledge needed for reading comprehension.

Johnson Elementary has a long way to go in improving reading—between 60-80% of students are below grade level and need some kind of reading intervention to get them where they need to be. Nearly all of the school’s teachers have been trained in the science of reading.

But even in the face of daunting challenges—including Covid school closures and the Jackson water crisis, which recently closed the school for nearly a week—efforts at improving reading are paying off, even if progress isn’t happening quickly. “I can say from our own internal benchmark data and anecdotal information that things are slowly improving,” said the school’s reading interventionist Jessica Crosby-Pitchamootoo.

Weathersby said having Cameron slow down and concentrate on all the pieces of the text has benefitted him—especially in writing, where his vocabulary and knowledge of grammar has grown.

“He’s even started correcting me, saying ‘Mom, you can’t use that word to start that sentence,’” Weathersby said, laughing.

The state of Mississippi has been slowly improving since a 2013 overhaul led to big changes in how schools teach reading. Between 2013 and 2019, statewide fourth grade reading scores rose by ten points, even for historically marginalized groups like Black and Hispanic students. They showed more growth in reading than any other state, and were one of the few states whose reading scores bounced back in 2022 after prolonged Covid school closures.

Once ranked dead last in reading achievement, the state’s upward trajectory was nicknamed the ‘Mississippi Miracle.”

Mississippi’s success can be attributed to multiple efforts—a new state education leader, Carey Wright, who reorganized the entire education department to focus on literacy and more rigorous standards; a big investment in teacher training in the ‘science of reading’; and two 2013 laws, one appropriating state dollars to fund pre-k, and the other requiring all third graders to pass the “reading gate” assessment or risk being held back.

“We used a multitude of strategies,” said Wright. “But the science of reading and accountability were our core pieces. Our accountability model deliberately focused on the bottom 25% of kids, we wanted to focus on the kids who needed it most.”

A recent series of changes and upheavals has some wondering whether Mississippi’s miracle can continue—including Wright’s departure from the state department of education, and the sunsetting of the Barksdale Reading Institute, a nonprofit that’s spent $100 million since it opened in 2000 helping remake how literacy gets taught in the state. Covid school closures and the Jackson water crisis have only added to the challenge.

Despite all the barriers, Mississippi is planning not just on keeping what they’ve got, but also expanding their initial efforts. This year the state expanded its science of reading efforts to middle school teachers, hoping to catch more students who continue to struggle. They also expanded the state’s innovative coaching model—adding digital coaches and early childhood coaches as well.

“Mississippi reading 2.0 is pressing forward,” said interim state superintendent Kim Benton. “We plan to continue what we know works while expanding and continuing to build out supports.”

In the overhaul’s early days, Mississippi invested heavily in training more than 19,000 elementary school teachers in phonemic awareness and phonics using the research-backed program LETRS, and then supported those teachers with intensive literacy coaching to help implement the new strategies in early reading classrooms.

But now districts are adding to those foundational skills, weaving in other aspects of the five pillars of literacy, like vocabulary, fluency and comprehension. Jackson Public Schools, for example, implemented the knowledge-building curriculum Wit & Wisdom in 2019, to address those gaps. Their literacy units often focus on science or social studies concepts that students might not be exposed to otherwise.

Even in a district where the science of reading had become common knowledge, the shift to knowledge-based curriculum, which research has shown to improve reading comprehension, posed its own challenges. Johnson Elementary interventionist Crosby-Pitchamootoo said she underestimated the size of the philosophical shift for many teachers who had been used to teaching comprehension as a set of skills like ‘find the main idea.’

“The part that has been really eye-opening and exciting for me is the knowledge piece,” Crosby-Pitchamootoo said. “What students need to be able to do is to deeply understand and discuss a complex text.”

Other districts are helping middle grade teachers (4th-6h grade) better understand how to incorporate the science of reading into classrooms mainly focused on content. In Rankin County School District this year, director of curriculum, instruction and professional development Melissa McCray launched a series of trainings for principals and teachers on how to weave pieces of structured literacy like morphology into algebra, world history and earth science.

When it comes to teaching the next level of literacy, “We know we can’t skip those grades,” McCray said. “But for them it’s more like, ‘How do I take a read-aloud and teach morphology and syntax? Those parts of words—in middle school, if we can teach the parts of words, they show up everywhere, in math and science class, they show up in literature, whether it’s informational text or narrative text.”

The state also partnered with Mississippi public television to create an on-demand channel of recorded lessons for PreK through 12th grade that run from 7 am to 7 pm every day, to help mitigate learning gaps from the pandemic.

Educators in rural districts who may not have the same access to training or coaches can watch videos of high school teachers teaching an English standard or math standard, how they differentiate instruction and tie their lessons back to literacy.

Even with a plan to close their doors in 2023, Barksdale is spending its last official year trying to move the needle in the one area the foundation believes could make the biggest impact on the future of state literacy: ensuring that Mississippi’s public universities teach the science of reading to pre-service teachers.

Over the last decade, Barksdale has been instrumental in helping the state create a minimum reading course requirement for pre-service teachers and developing a cohort of LETRS-trained professors and instructors at the university level. But while presenting the new knowledge was one thing, encouraging longtime faculty with EdDs and PhDs to implement and champion the science of reading in education courses has remained a stubborn challenge.

Training preservice teachers in the research behind how the brain learns to read and how to implement it before they arrive in classrooms would save the state millions, said Barksdale CEO Kelly Butler. The foundation conducted several studies showing how little time universities spent on the science of reading, then leaned heavily into training and literacy coaching aimed at university faculty.

For faculty members like Billie Tingle, a former second-grade teacher who has been teaching reading foundation courses at the University of Southern Mississippi for seven years, LETRS training was a “life-changing” experience. She went into it thinking she already knew most of the material, but was shocked at all she didn’t know. “I was so naive,” Tingle said. “After the first day [of training], I remember thinking, ‘I’m never going to be the same.’”

But it was the coaching that helped put her new knowledge into practice. Her coach Antonio Fierro, Barksdale’s now-former chief impact officer for educator preparation and curriculum, not only co-taught with Tingle and provided feedback from lessons, he also helped with other tasks like selecting science of reading-aligned textbooks and remaking course syllabi.

“Coaching is still the best way to ensure that the elements [of the science of reading] are going to be implemented,” Fierro said. “I was able to visit classrooms, model instruction. In some cases, I’d go back and team teach with them, and the final process was them teaching and letting me provide feedback. It becomes not only the science of reading-—it becomes the science of teaching as well.”

Even though Barksdale’s literacy work will continue in a different form, Butler said she hopes their two decades of helping to implement the science of reading changes how colleges of education in Mississippi view their mission. “One thing it’s going to take is for colleges of ed to see their product as k-12 achievement, and not a certified teacher,” Butler said. “Faculty needs a safe place to acknowledge what they don’t know, and a safe place to learn it together.”

Tenette Smith, Mississippi’s executive director of elementary education and reading, remembers what it was like when the state first decided to overhaul its approach to literacy nearly a decade ago. She said she traveled all over the state, from “the cotton fields to the coast,” talking to teachers and principals about the science of reading.

“Sometimes I had principals who were old football coaches who’d never even heard of an anchor chart,” Smith said. But slowly, in small increments, things began to change.

After years at the bottom, Mississippi’s reading scores are now consistent with the national average. Their turnaround model of training, coaching and implementation is being adopted by a variety of other states, including Alaska and North Carolina, looking to improve their literacy rates.

With the foundations of reading firmly in place, teachers like Barquita Stanton in Jackson are trying to smoothly transition students from learning to read to reading to learn. During a recent unit called The Sea, Stanton’s third graders watched videos on shipwrecks, learned about divers and oceanographers, and tried to figure out the answer to questions like ‘why do scientists study the sea?’

Their “choral reading” for the unit was from The Fantastic Undersea Life of Jacques Cousteau. Stanton had students circle the vocabulary words, take notice of punctuation, and follow the text along with their fingers.

“We are learning to read those complex texts, going way into detail and breaking it all down as much as possible, so my students can understand it better while still making it fun,” Stanton said. “I love hearing them choral read.”

Holly Korbey is an education and parenting journalist writing about teachers, parents, and schools for a national audience. She is the author of Building Better Citizens, and her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Boston Globe, Medium's Bright, Brain, Child Magazine, Babble, The Nervous Breakdown, the essay collection How to Fit a Car Seat on a Camel and others. She is a regular contributor on education for Edutopia as well as NPR's MindShift blog, out of San Francisco member station KQED. She's also been nominated for an Education Writers Association award for outstanding reporting on how dyslexia is handled in schools. Holly writes and speaks on issues happening inside classrooms, including the 'new civics' education, the arts, dyslexia and reading and more. Born and raised in Evansville, Indiana, the daughter of a junior high history teacher and a balloon artist, before journalism Holly worked professionally as a musical theater actress in New York City. She now lives in Music City, USA, with her husband and three sons. She can usually be found reading a book at Little League practice.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.