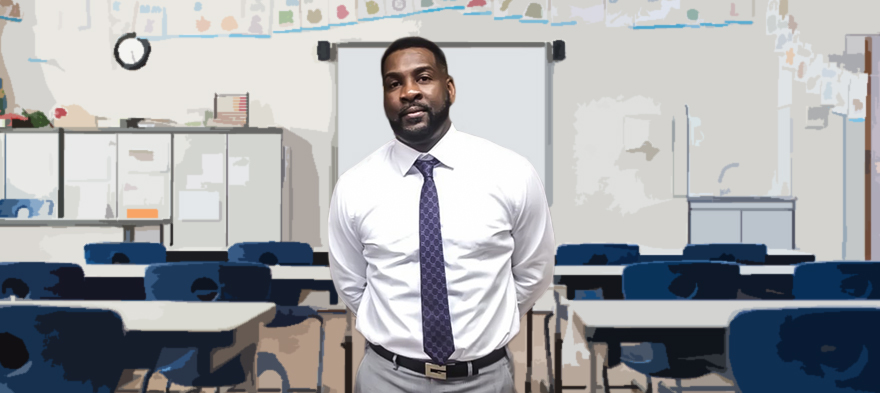

Back in 2013, when Principal Aaron Rucker first came to Auburn Gresham’s Ryder Elementary, he said someone in the central office warned him: “You’re being set up for failure.” At the time, Ryder was on the list of schools being considered for possible closure. But none of this deterred him.

At the time, he told DNAInfo, “My long term goal is to be a premier Level 1 school.” While parents and alumni led the charge to save Ryder, Rucker worked behind the scenes to start moving the school forward. “The alumni and the Parent Advisory Council were the voice to keep the school open. But I didn’t want to lay down and die. My way to help us was to improve culture and climate.”

When Chicago Public Schools decided to close neighboring Morgan Elementary, enrollment doubled and it took a while for the faculty and students to overcome decades of rivalry and bond. Nevertheless, [pullquote]by the end of the first year of the merger, Ryder had jumped two performance levels and reached Level 1 in district ratings.[/pullquote] In 2015, Ryder came off probation status, after seven years of “intensive support.”

Last year, Ryder achieved the district’s highest performance designation, Level 1+, primarily due to students’ growth and attainment on the NWEA MAP test. Students are achieving at and above grade level, learning growth is among the highest in the nation. In surveys, teachers, students and parents give Ryder high marks for ambitious instruction and a supportive, safe environment.

How did Ryder do it? According to Ryder teachers, it’s because Rucker works tirelessly to support them. Veteran teacher Kim Anderson, one of only two teachers still on staff since before Rucker became principal, tangled with him at first. But his willingness to put money into classrooms and build relationships with teachers won her over.

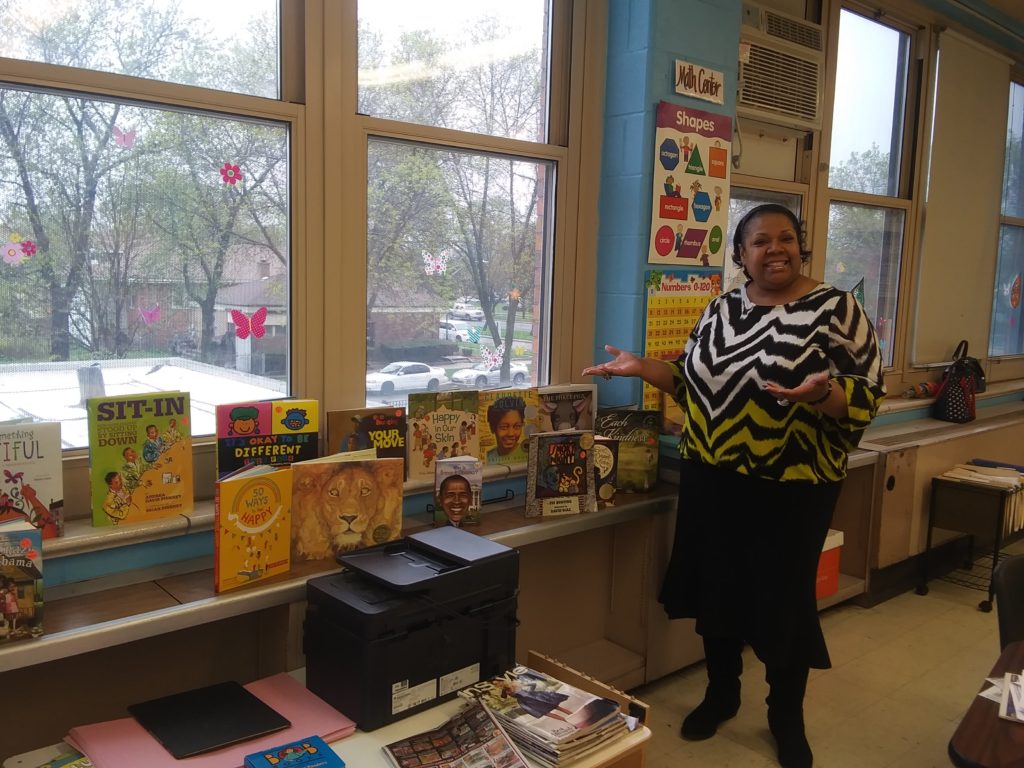

Anderson recalled speaking up in a faculty meeting to tell Rucker about her change of heart. “I cussed your name ‘til I got tired, but I’m here to say thank you. You have given us everything we need to teach these children.” Anderson pointed first to his willingness to provide tables for centers and books for the library in her first grade classroom, then noted, “That is coupled with relational shifts in the building.”

Middle-school teacher Kishonda Sims exemplifies those shifts. “I just popped into Anderson’s class and saw something she was doing that might work for my kids. Ms. Anderson has been a huge sounding board for me.” Plus, Anderson’s mentoring isn’t an outlier, Sims noted. “I can’t think of a teacher who doesn’t have two or three other colleagues they can go to and talk about pedagogy.”

Other teachers point to Rucker’s coaching ability and relentless drive to help them grow professionally. Diverse learner teacher Kelli Stanley is one of a number of Ryder teachers who were ready to give up on the profession before they found Rucker. Now, she says, she’s earning a second master’s degree in educational leadership and plans to become a principal herself.

Rucker’s leadership and Ryder’s team culture made the difference, Stanley says. “He took time to explain things, discuss best practices. That’s what keeps me at Ryder, knowing the principal wants to help me grow. [pullquote]He builds a team, a community. He finds out people’s goals and whatever he can do to help them get there, he does it.[/pullquote]”

During a tour of the school, Rucker took me to the third floor, where a teacher was working in the hallway with a group of four middle-school boys. “Sometimes she can go down to one-to-one,” said Rucker, who added she is one of his best teachers and he put her with this group on purpose. The young men, all new to Ryder, had struggled in their previous schools.

Rucker, who taught diverse learners for a while before becoming a principal, also takes a hand in working with those small groups, Stanley told me. “I like the way he takes the time to work with them himself.”

Now that Rucker has achieved his goals for Ryder’s ratings, he hopes his work will help him attain his next professional goal—winning the Golden Apple Foundation’s Excellence in Leadership award for principals. To do that, he’s staying focused on coaching. Back in his office, he showed off his bookshelf, which is loaded with books on the topic. “This is like two percent of my collection. You should see my house,” he said, smiling. “I had to order new shelves.”

Then Rucker quoted a well-known saying among principals: “If you don’t feed the teachers, they’ll eat you.” The saying reminds him to stay focused on his top job: keeping his teachers well-fed professionally, so they can help students reach their full potential.

Maureen Kelleher is Editorial Director at Future Ed. She was formerly Editorial Partner at Ed Post and is a veteran education reporter, a former high school English teacher, and also the proud mom of an elementary student in Chicago Public Schools. Her work has been published across the education world, from Education Week to the Center for American Progress. Between 1998 and 2006 she was an associate editor at Catalyst Chicago, the go-to magazine covering Chicago’s public schools. There, her reporting won awards from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the International Reading Association and the Society for Professional Journalists.

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

Your donation will support the work we do at brightbeam to shine a light on the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.